I finally stopped nitpicking the World War 3.2 manuscript long enough to send a proof copy to my rock-steady crew at Patreon. If that includes you, check your email for the freebie.

That took a lot longer than expected, mostly through my own choices. As soon as I decided to go wild and write as many fucking words/chapters/books/whatever as I needed to finally wrap this thing up, my outline for 3.2 became obsolete. I started asking myself, since space was no longer an issue, where could I go with this thing?

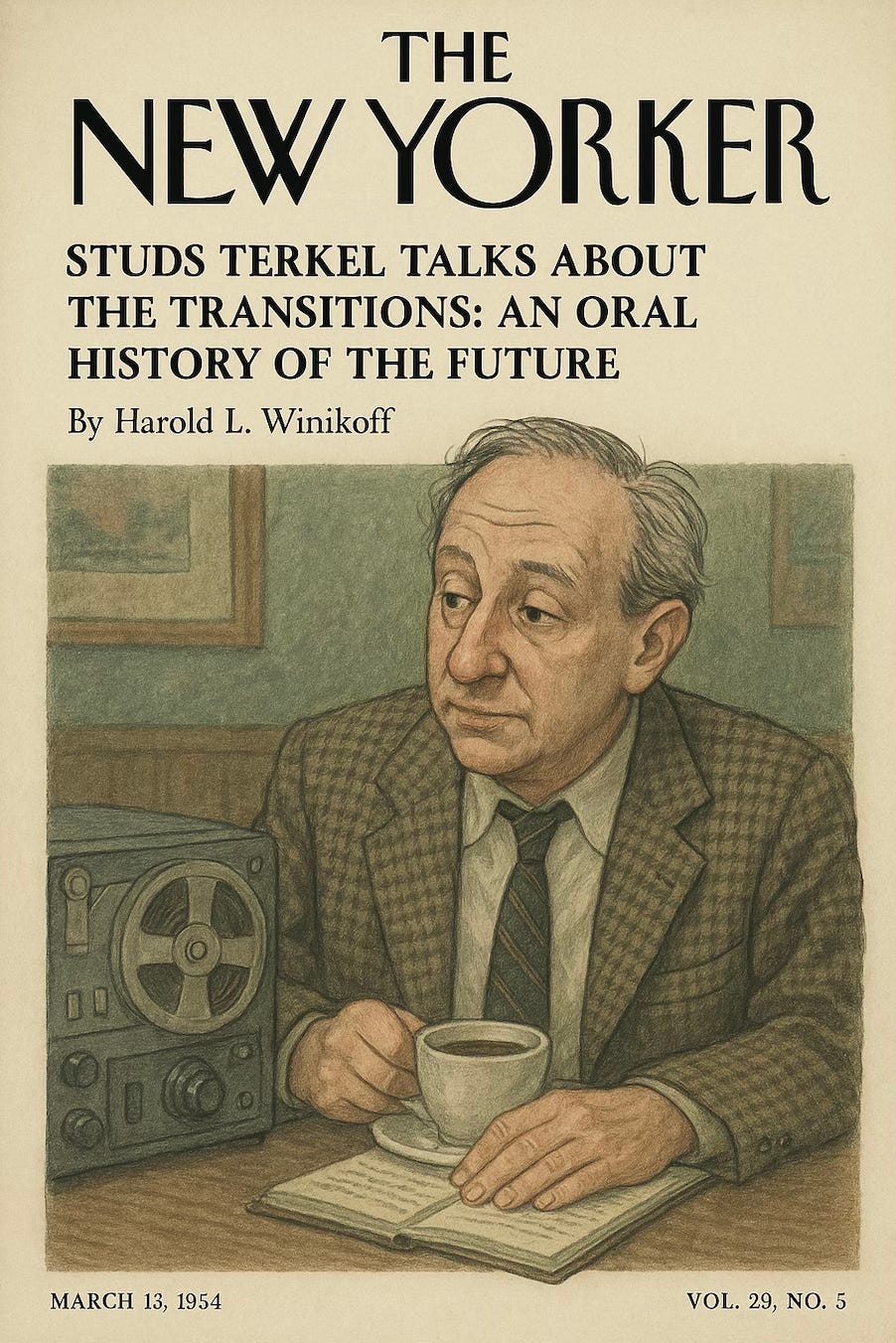

One place was an alternate version of The New Yorker, from 1954. An interview with Studs Terkel about his oral history of the Transition. I wrote a bunch of ‘extracts’ from the book and the magazine and salted them through 3.2 whenever I wanted to thicken up the world-building.

Here’s the intro to the first extract…

‘Studs Terkel Talks About The Transitions: An Oral History of the Future’

By Harold L. Winikoff

The New Yorker | March 13, 1954 | Vol. 29, No. 5 | pp. 51–66

Louis ‘Studs’ Terkel orders black coffee in a bar on 57th, a corner joint with a taxidermied pheasant behind the register and a piano that hasn’t been tuned since the last war. It’s late afternoon, and the windows are fogged from the inside, thick with the kind of secondhand smoke and first-rate banter that Terkel seems to carry with him like static charge.

He’s wearing a scuffed houndstooth jacket, baggy at the shoulders, and he carries a tape recorder heavy enough to bend the table legs. He sets it down but doesn’t turn it on. Instead, he produces a notebook with dog-eared pages and flips through it like a gambler working his patented system at the track. Terkel is not, by his own admission, a historian.

“I'm a listener,” he says. “That’s the whole secret. Shut up long enough, and people will tell you everything.”

We’re talking about The Transitions, his forthcoming oral history of the last decade and change. He’s reluctant to call it a book yet. It’s more of an excavation, he says, and some of the bones are still warm.

“The generals have their maps. Scientists have their microscopes. What I’ve got is a waitress in Akron who dreams about flying in a space shuttle. A pipefitter in Queens who swears the sun’s a different colour now. And this kid in St. Louis who talks like he’s sixty and writes like he’s twenty-one in 2025.”

Terkel’s eyes crinkle when he smiles, which is often, but it never quite erases the shadows underneath. He’s been travelling more or less nonstop since late ’52, chasing stories through church basements, union halls, student lounges, jazz clubs, and military depots. What he’s teased out is less a straight line than a messy braid of voices: astonished, furious, adrift, hopeful and haunted.

“I’m not trying to explain the Transition,” he says. “That’s someone else’s job. Professor Einstein, maybe. I’m just trying to remember it while it’s still happening. Before people start making up stories instead of just telling them.”

There’s a pause while the bartender—sensing something unusual is underway—delivers a second coffee.

“I’ll tell you this,” Terkel says. “If we’re to get through this—and that’s still an open question—we’ll need more than physics and math to explain what happened. We’re gonna need voices. Real ones.”

He takes a sip, grimaces politely, and returns to his notes. “Anyway,” he says, “enough about me. Let’s listen to someone else. You’ve heard of this Kerouac kid, right?”