As I said last time, Anthony Albanese has succeeded in making Labor the natural party of government in Australia, relegating the rightwing opposition to the role of “B team” and marginalizing the Greens and progressive independents. The cost has been the abandonment of Labor’s historic role as the “party of initiative”, pushing against the conservative “party of resistance”. Indeed, the reverse is now closer to the truth

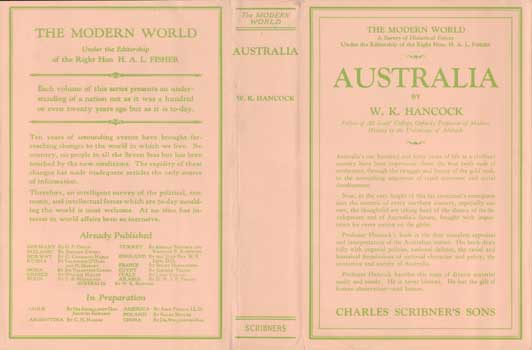

The characterisation of Labor as the party of initiative goes back to WK Hancock’s 1930 classic Australia (though he used the phrase “party of movement”) and was broadly accurate both as a description of his own time (when the Labor party was only 40 years old) and for nearly a century afterwards. Hancock wrote at a bleak time for Labor. Having achieved many of its early goals, such as union recognition, workers compensation and the expansion of public enterprise, Labor had split bitterly over conscription in the Great War of 1914-18 and was in the process of splitting again over policy responses to the Great Depression.

But these setbacks proved temporary. The Curtin-Chifley and Whitlam governments were responsible for most of the policy innovations of the post-1945 era. Curtin and Chifley secured legislative independence by adopting the Statute of Westminster in 1942 introduced uniform federal income tax upheld by the High Court’s First Uniform Tax case in July 1942,expanded social security and launched a mass immigration program under Calwell that reshaped the population, Labor founded key institutions including the ANU, national airlines and research bodies), and capped the program with the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme in 1949.

Most importantly, Labor committed the Commonwealth to full employment in the 1945 White Paper on Full Employment. The central role of the national government in ensuring full employment legitimised a wide range of interventions in the economy.

Even in opposition from 1949 to 1972 , Labor continued to set the policy agenda. With limited exceptions, the Menzies and his successors preserved\ the foundations laid by Curtin and Chifley, and responded, grudgingly, to pressure from Labor and its intellectual allies

The high point of Labor as the party of initiative came after Whitlam’s election victory 1972. In his first few weeks in office, Whitlam did more than we have seen in the lifetime of the current government: including ending conscription, withdrawing Australian troops from Vietnam, and abolishing tertiary education fees. His government established Medibank (the precursor to Medicare), introduced the Racial Discrimination Act that finally ended the White Australia policy, created legal aid, established land rights for Indigenous Australians, introduced no-fault divorce, legislated equal pay for women, and dramatically expanded federal funding for schools and universities. The Fraser conservative government managed to wind back some of these measures (Medicare was almost eliminated, for example) but not many.

The Hawke-Keating government, gaining office as the neo-liberal counter-revolution become dominant, reversed the work of previous Labor governments in some areas, such as privatisation and deregulation Butit carried on the progressive agend in other areas, including the establishment of Medicare on a permanent footing, the extension of superannuation to the entire workforce, and reconciliation with indigenous Australian. Whatever the direction of movement, there was no doubt that Labor continued to see itself as the party of initiative. Nearly thirty years after its defeat, the Hawke-Keating era is still seen by many as the classic period of reforming government.

Even during the chaotic Rudd-Gillard years (2007-2013), Labor achieved transformative reforms Rudd’s achievements were both symbolic (the National Apology to the Stolen Generations) and practical (the GFC stimulus and the National Broadband Network). Gillard’s government introduced the National Disability Insurance Scheme, perhaps Labor’s greatest social reform since Medicare. legislated carbon pricing, implemented the Gonski education funding reforms, established Australia’s first paid parental leave scheme, introduced plain packaging for cigarettes, and launched the royal commission into institutional child abuse.

In opposition after the disastrous defeat of 2013, Labor continued to drive the policy debate. Bill Shorten’s campaigns in 2016 and 2019 offered substantive progressive platforms. His proposals to reform negative gearing and franking credits directly addressed housing affordability and tax fairness, threatening entrenched interests. He campaigned on ambitious climate targets and a genuine transition to renewable energy. His tax reform agenda sought to make Australia’s system more progressive and equitable.

Labor drew the lesson that bold reform loses elections. But this conclusion reflected a fundamental misreading of Shorten’s defeats. His policies were economically sound and addressed real problems. The narrow loss stemmed from Shorten’s personal unpopularity, poor campaign execution, and Queensland’s particular hostility to change, exacerbated by the disastrous intervention of Bob Brown’s Stop Adani convoy (has there even been a “convoy” protest that’s been other than counterproductive?). The fact that all the polls herded together with a prediction of a narrow win increased the shock of arising from a narrow less. The tragedy is that Labor abandoned policy ambition altogether rather than ditching a few unpopular policies and trying again..

The personal role of Anthony Albanese was crucial here and remains central to our understanding of the issues. Even before the 2019 election, Albanese was positioning himself as the rightwing alternative to Shorten. His factional history as the leader of the NSW “Hard Left” in the 1990s gave him the cover he needed here.His [dominance over Labor’s factions](https://theconversation.com/albaneses-small-target-strategy-may-give-labor-a-remarkable-victory-or-yet-more-heartbreak-166752) reflects this calculation: the Left has been neutered by their own leader’s rightward stance, while the Right has been co-opted by a leader who governs like them while retaining Left credentials. A different leader, like Jim Chalmers, might do a bit more, but that remains to be seen.

Labor’s record in office since 2022 speaks for itself, or rather, its silence speaks volumes. With a handful of exceptions, the Albanese government has done little more than implement, with tweaks the appallingly bad policies inherited from nine years of LNP government, several of which were yet to be implemented when Labor took office. Labor’s defence policy is centred on Morrison’s AUKUS agreement, its tax policy a slightly modified version of Morrison’s three-stage program, its climate policy a modification of Abbott’s Safeguard Mechanism, its higher education policy the consolidation of Tehan’s appalling “Job Ready Graduates” system.

The thin record of Labor’s own policies is also instructive. Before the 2022 election, the promises that most excited its supporters were the Housing Australia Future Fund (HAFF), the National Anti-Corruption Commission and the Voice to Parliament, a revived and reformed ATSIC which would be entrenched in the Constitution. HAFF was, and remains, a jury-rigged mess, yet to construct a single house. The NACC has been notable only for its own scandals.

The Voice referendum, always facing long odds, was doomed by Albanese’s refusal to explain how it would work (the infamous “details”). The reason, I believe, was that Albanese was unwilling to admit that it would fill much the same role as ATSIC, and would face the same rightwing attacks, as indeed it did.

On the original “three-term” theory put forward by Albanese’s advocates, the caution of the first term in office was supposed to cement Labor’s hold on office, laying the ground for transformative change in the second and third terms. The 2025 election did more than cement Labor’s position, it buried the opposition under thick layers of concrete. But the glacial pace of reform seen in the first time has now frozen into solid immobility. Even broadly popular proposals like a ban on gambling ads have been forgotten.

And even where action can’t be avoided, Labor is still deferring to the LNP. Rather than reach an agreement with the Greens, correctly recognised as Labor’s true enemy, the preferred approach for legisation is to reach a “bipartisan” agreement with the LNP. From an initially centrist position, the result is a centre-right legislative program.

Nothing lasts forever. As Wayne Swan recently conceded, Labor’s win in 2025 was “wide but shallow”. Not only was the primary vote low, but enthusiasm among its supporters has dwindled to nothing. Swan’s closing reference to the need for Labor to mobilise “Activists, organisers and agitators who are active and more engaged with their local communities” is an implicit concession that activists and organisers no longer see the Labor party as a vehicle for positive change. https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/albanese-s-election-win-wide-but-shallow-labor-president-s-frank-admission-20250921-p5mwqh.html

Returning to Hancock’s characterisation of Australian politics, Labor is now, above all, the party of resistance, fighting off both the populist right and its former activist base, now to be found with the Greens and community independents. The parties of resistance have held office most of the time since Australian federation, but their adherents can point to little in their history of which they can be particularly proud.

A couple of notes on this piece

1. Back in the paleolithic era of blogging (circa 2003), I used to call Tim Dunlop my “blogtwin” since he and I regularly posted similar ideas. That’s continued into the Substack era, as you can see in this excellent piece

Labor as the party of resistance2. I’ve experimented with Genspark AI in preparing this piece. I first set up an agent trained on my own work to write in an approximation of my own style. Then I told it to write a draft – this part of the package appears to be a front end to OpenAI’s Deep Research. The “John Quiggin agent” did an OK job, better than most of the political commentariat, but I didn’t use much of what it produced. OTOH, I got some useful lists of policy actions and some links I hadn’t seen.