The purpose of this submission is to respond to the National Electricity Market Wholesale Market Settings Review Draft Report, released in August 2025. The purpose of this submission is to argue that the ad hoc interventions seen so far should be replaced by centralised long-term planning of investment in both generation and transmission.

The National Electricity Market (NEM) was designed to combine day-to-day matching of electricity supply and demand with the provision of market incentives for efficient investment. As the draft report concedes, the NEM has failed in the second of these tasks. The report’s analysis of this central issue (pp 38–39) consists of two paragraphs, which may be quoted in full, along with the relevant figure

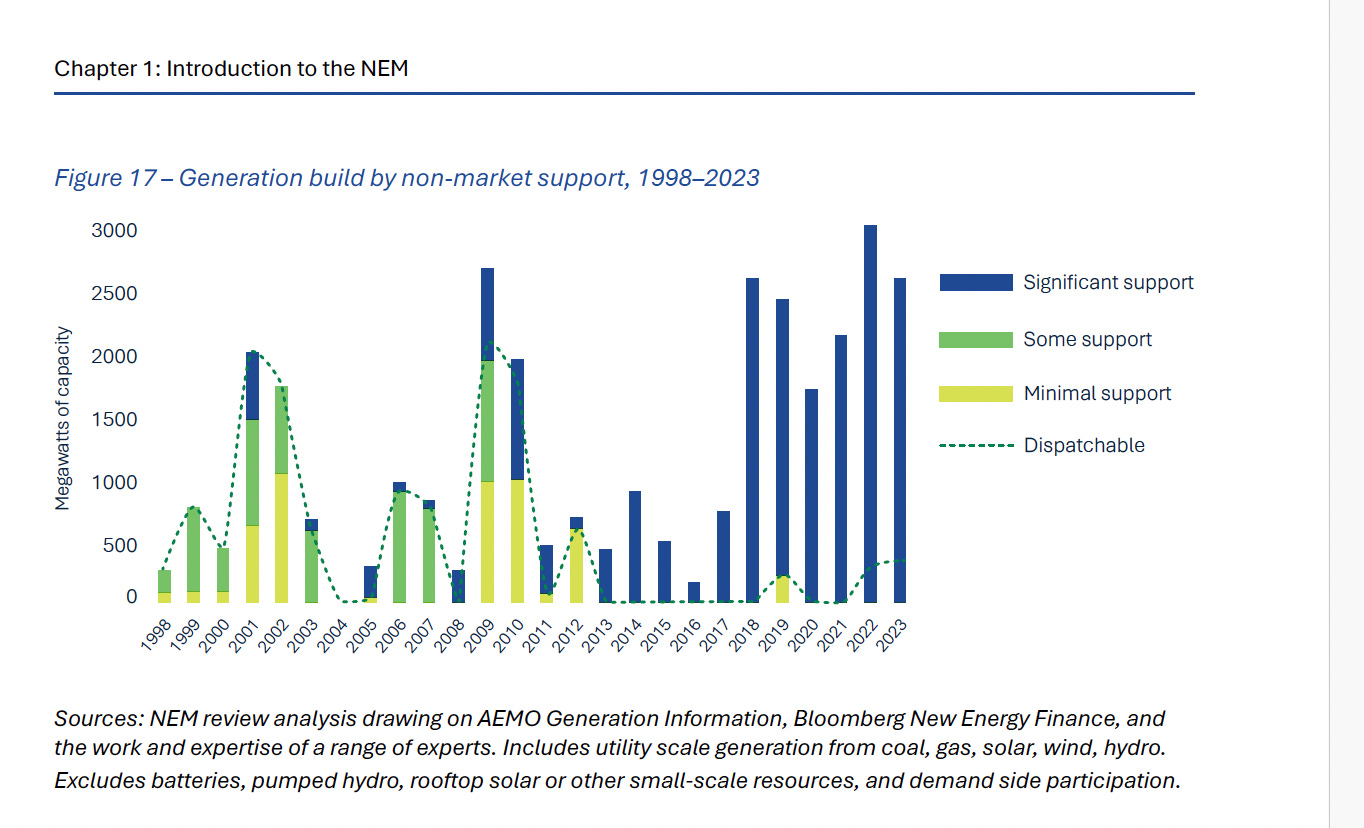

Investment in new generation in the NEM has been uneven – and in large part driven by specific policy measures. Investment in new generation in the NEM has fluctuated significantly over time, both in scale and by technology type. These shifts can be broadly grouped into three distinct periods since the market’s inception: a phase of growth driven primarily by rising peak demand (1998–2011); a period of oversupply and limited new investment outside of renewables mandated by the expanded Renewable Energy Target (2011–15); and the current phase of transition towards a low-emissions system (2015‑present) (see Figure 17).

Although the design of the NEM aimed to let market forces drive investment decisions, government policy support has been a significant driver of investment in new generation since its inception. The Panel notes that this has been a feature of most deregulated electricity markets, irrespective of the market design adopted. Almost all investment in new generation capacity in the NEM has received some form of government support, and there are very few examples of pure, market-only investments that were made entirely on the basis of expectations about future spot market revenues and forward derivatives markets. Emerging research suggests NEM spot prices and derivative markets on their own have not driven recent investment decisions in the NEM, in contrast to the strong role of policy support.

Given that it is investment decisions, rather than day to day market operations, which drive the energy transition, this outcome is entirely unsatisfactory.

The treatment of investment is further weakened by the exclusion of transmission from the scope of the report. However, the report correctly notes (p 36) “Centralised, long-term planning is essential to ensure transmission investment occurs in the right places, at the right scale and with sufficient lead time ”

The purpose of this submission is to argue that the ad hoc interventions seen so far should be replaced by centralised long-term planning of investment in both generation and transmission.

The dual roles of the National Electricity Market

The NEM was introduced in the 1990s, at a time when the primary sources of electrical generation were coal and gas. In the early years of the NEM, there was an oversupply of generation capacity as a result of expansion during the 1980s which was regarded, in retrospect, as excessive “gold plating”.

The NEM was designed to fulfil two purposes. First, on a day to day basis the NEM matched supply and demand in real time, using supply schedules submitted by generators. In this function it was reasonably successful until recently, although concerns were raised about strategic behaviour by suppliers with market power.

The second function was to promote efficient investment decisions. A sustained period of high prices would provide a signal to investors that construction of new power stations would be profitable. The design of the NEM was reasonably well suited to provide market signals for investment in “always-on” coal-fired power stations which would receive roughly the average daily price. In practice, however, new investment in the 1990s was limited except in Queensland, where the electricity industry remained publicly owned.

The design was much less satisfactory in relation to gas-fired power, which is best suited for “peaker” operation. This is because the NEM price is subject to a cap, originally referred to as the “value of lost load”, which was initially set at $5000/MWh. Although this might seem like a harmless restriction, the profitability of investments in peak capacity depends to a large extent on the relatively rare occasions when market demand exceeds supply even at such high prices.

The most important fault of the pricing system was that it made no allowance for carbon emissions, even though the introduction of the NEM coincided with the adoption of carbon emissions targets. The assumption, presumably, was that this issue would be addressed through some other policy, such as an economy-wide carbon price. In practice, however the only effective mechanism was the Renewable Energy Target (RET), the first of many adjustments bolted on to the simple design of the NEM.

Over time, as noted in the Review, the NEM has become less and less useful as a guide to investment. An electricity supply industry involving a mix of carbon-based and carbon-free suppliers raises a complex mix of issues including system stability, storage and access to transmission networks. The relationship between the prices set in the NEM and the incentives facing both utility scale investors and households regarding solar and wind investments are opaque to put it mildly.

An alternative approach

Rather than continuing to tweak the parameters of the NEM in an effort to get investment decisions right, it would be better to confine the NEM to the function of setting wholesale electricity prices so as to equate supply and demand.

In the place of the NEM, the optimal solution is a publicly controlled National Grid responsible for planning and managing investment in generation, transmission and large-scale storage.

Investment would generate returns through a mixture of revenue from electricity sales on the NEM and capacity payments designed to ensure system stability. The planning authority would approval proposals put forward by investors, and would also identify unmet needs and call for tenders to meet them.

Exclusive reliance on private investment has been a failure, leading to the re-establishment of public enterprises in Victoria and NSW and the expansion of public investment into renewable energy through CleanCo in Queensland. The public role should be expanded further while allowing scope for private investment at utility scale and also for households to meet their own needs through rooftop solar, storage and potentially, virtual power planets at the local level.